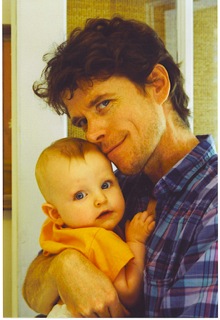

Megan Stielstra, author of: Once I Was Cool, personal essays

Age of kid: 6 years

What was your writing schedule (ideal and actual) like before kids, and how has that changed?

My writing schedule—my schedule, period—is a bit all-over-the-place. I’ve always had two or three jobs at the same time, and I’d write whenever I could. Sit down and get to it—which in retrospect was pretty good training for being a parent. Now, I have less time, but I use it better, so it’s an okay trade-off.

I’ve also found that, for me, it’s less about Before Kids/After Kids and more of a constant acceptance and adaptation to change. I just looked back at an essay I wrote about my writing process when my son was three, and it was entirely different than it is now. I don’t want to jinx myself by saying it’s easier, but he’s in kindergarten, and is more interested in books and Legos and karate than in, say, jumping off the balcony or setting the curtains on fire. He’ll say, “Listen, I’m going to sit here and build a skyscraper, and you sit there and write something.” The challenge now is, I want to build the skyscraper, too. Building skyscrapers is fucking awesome.

How do you remain present for your family even when you’re sunk deep into a current project?

It’s either all in or all out. When I’m with him, I want to really be there, down on the floor with the skyscrapers. For me, it’s easier to write somewhere else; at work on my lunch break, commuting on the L, or down the street at the coffee shop, one of a hundred open laptops.

I’m very lucky to have a partner in this, so we try to divide and conquer. On weekends, when we’re all home, he hangs with our son in the morning and I work; at lunch time we switch; and all together for dinner. It’s not always as neat as that, of course, but we try.

How has parenthood changed the work itself, if at all?

It definitely changed the work. Suddenly I was writing… not about parenting exactly, but about this new lens I was looking through, like how you put on tinted sunglasses and suddenly everything is purple. I remember listening to The Woods, that Sleater-Kinney album, and there’s a track called “Modern Girl” that goes “my baby loves me, I’m so happy…” I’d listened to it probably a thousand times, but after my kid it was like, Okay. Wait. What baby are we talking about here? I heard music differently. I read books differently, seeing through the eyes of being a parent as opposed to having been parented. Same with film, art, theater. There was a whole new level of inquiry, new ways to consider love and life and language, and—I’m not quite sure how to explain this so stick with me for a second—it upped the ante. I have something now that’s sacred, and I want to be better for him; better mom, better writer, better human being on this planet, and I want the world to be better, too. I believe that art has a place in that. So what am I going to do about it? What am I going to make? How can I help other artists make stuff?

It’s all this lovely, profound sort of mind-fuck. I’m trying to figure it out on the page. I’ll always be trying to figure it out.

What is the most challenging aspect of being a working artist and a parent?

Time.

Do you have any advice to other writers with kids or who plan to have them?

A few years ago, I spent some time at an artist residency. It was my first substantial length of time away from my son. I had plans that were so high-stake, so high-pressure: finish a draft of my book, get back into a day-to-day writing process, and something that I referred to as “conceptualize next project,” a phrase that nearly sent me into a panic attack whenever I looked at my to-do list. Know what I did that first day at the residency?—slept. For, like, eighteen hours straight. Then I binge-watched season three of Trueblood on my laptop, twelve episodes without stopping. Then I cried for the time I’d wasted. Then I cried because I missed my kid. Then I cried because Tara was mad at Sookie. In the end, I scrapped my plans, went for walks, stared at the wall, read a ton, and finished one short essay about postpartum depression.

In every room at the residency, there are spiral notebooks where artists can document their time. On my last day, as I was packing to leave and berating myself for how little I’d accomplished, I flipped through that notebook, reading wisdom and advice from writers who’d worked there before me. Thrillingly, I found a name I not only recognized, but emulated; a poet and playwright whose work consistently blew me away in its honesty and bravery, not to mention the sheer quantity she produced while raising her daughter and working full-time. She’d been there, in that very room! Sleeping and reading and creating, just a few months before! I dug into her words, expecting to find something about the project(s) she’d completed, or maybe some profound musings on the artistic process. Know what she wrote about instead?—sleeping. Staring at the wall. And—I shit you not—watching Trueblood on her laptop, and what was up with Sookie?

I shy away from giving advice to writers and to parents. We have different situations, different processes, different challenges and expectations. That said, I think what I learned at that residency might apply to all of us: be gentle with yourself. The writing process is more than building sentences.

Also: Don’t compare yourself to other writers. That’s the true death, as the Vampire Authority says.

Also: That one short essay I berated myself for ended up being chosen for The Best American Essays. Truly, who knows what will happen?